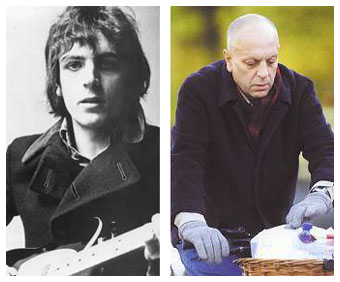

It’s interesting to see what creativity sparks from a single photograph; Tom Stoppard wrote Rock “n” Roll based on a photo he saw of an aged Syd barrett (co-founder of Pink Floyd) at age 60, riding his bike in London, carrying groceries in the baskets. Struck by the dichotomy of Barrett’s photos from the 60s, which show him at the height of his popularity and beauty, the strong contrast of the icon to the ordinary was overwhelming and he had to write about it. “I could see and hear the ghost of a play set in a suburban semi (which in England means half a house in a street of houses halved as symmetrically as Rorschach blots and occupied by people who are definitely not rock gods), and here, in my play, the reclusive middle-aged “crazy diamond” would … er, do what, exactly?” The article in Vanity Fair is great.

Before Richard Powers became a novelist, he was working in Boston as a computer programmer. One day while strolling in the museum he was so struck by the August Sander photograph, “Three Farmers” he quit his job, took two years and wrote Three Farmers on the Way to a Dance”…. his first novel about the men in the photograph and a man who studies the photograph. “One Saturday, I went to see a show of a German photographer whom I thought I had never heard of before. It was the first American retrospective of his work. I remember very vividly walking into the exhibition room and bearing to my left and seeing this photograph on the wall that instantly seemed recognizable to me. Three young men in Sunday suits, looking out over their shoulders as if they had been waiting there for seventy years for me to return their gaze. I leaned forward to read the caption, and the picture was named, “Young Westerwald Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, 1914.” The words went right up my spine. I knew instantly not only that they were on their way to a different dance than they thought they were, but that I was on the way to a dance that I hadn’t anticipated until then. All of my previous year’s random reading just consolidated and converged on this one moment, this image, which seemed to me to be the birth photograph of the twentieth century. This was a Saturday morning, as I said, and I went down on Monday and gave two weeks’ notice on my job. I can’t say that the book that emerged was exactly the book that appeared to me in that moment of recognition, but it was close. It certainly had its genotype intact. This quote is from an interview with Jefferey Williams in 1998.

Harun Forocki, the great German documentary filmmaker was struck by the a photograph of a woman in WWII, if you block out the figures around her, she could be an everyday woman simply on her way running errands, yet if you see the photograph in it’s entirety, she is in a concentration camp, next to a line of men with yellow stars being interrogated by an SS officer. His film Images of the World and the Inscription of War addresses how the brain absorbs visual information and how it processes images, recognizing and/or developing misconceptions.

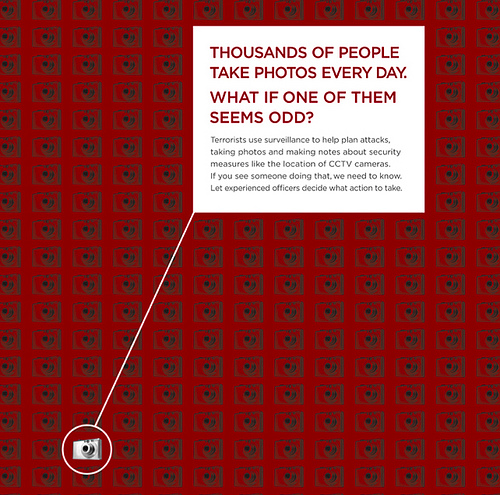

Errol Morris, the documentary filmmaker, has an interesting blog at the NY Times, about photography. Rather obsessive and sometimes a bit too analytical it is nevertheless very interesting at times. “I have beliefs about the photographs I see. Often – when they appear in books or newspapers – there are captions below them, or they are embedded in explanatory text. And even where there are no explicit captions on the page, there are captions in my mind. What I think I’m looking at. What I think the photograph is about.”

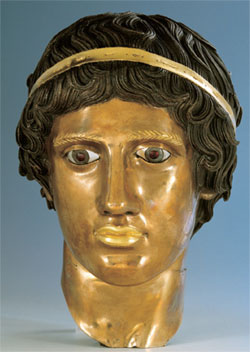

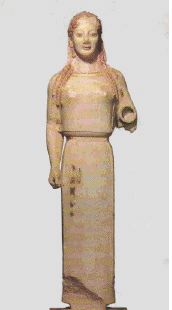

Here’s the Peplos Kore, the original statue–ghostly, poised yet

Here’s the Peplos Kore, the original statue–ghostly, poised yet